Offsite

James Lee Byars: I Cancel All My Works at Death

Written & Directed by Triple Candie

with dramaturgy by Jens Hoffmann

Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit

(February 7 - May 4, 2014)

A catalogue is available from D.A.P. (artbook)

* * *

The Auditorium

An evening in the near future.

The body of the Detroit-born artist James Lee Byars has now fully disintegrated in its unmarked grave in Egypt, 5921 miles from where it was conceived. No one alive has met him. He is spoken of like a dream, an illusion, a bubble, a shadow, a dewdrop, a lightening flash. No one has witnessed his “plays”. A few have heard stories—conflicting stories. They have seen photographs. They imagine.

In the wings and hallways of a crumbling auditorium, an amateur theater company is preparing for a production about Byars’s plays. For months, they have been reading his obituaries, re-writing his scripts, gathering props, sewing costumes, and auditioning actors. Tonight, the hall is dark.

From a gold throne, before a tattered curtain, the ghost of James Lee Byars rises like smoke through a hole in the roof.

Casting Department

A

provisional casting office has been set up with furniture cobbled together from an office supply warehouse. There is a chrome-lined black desk, topped with a pink rotary phone. On a putrid green wall—quite tall—are tacked casting portraits. Collectively, not individually, they depict the chimera-like James Lee Byars. On the desk is a flyer. The environment is strictly functional, the objects anachronistic. The tableau evokes a vague, unlived past.

...................................................SHELLY

Byars was dandy. He was erudite, but pretentions and arch. Like Goethe’s Young Werther, I find him amusing in death but I would have hated him in life.

.....................................................JENS

I agree, though he did have a funny way of talking, which I quite like. He always ended his statements with a question— “don’t you think?” or “no?” It reminds me of a Zen Buddhist speaking in koans. Or perhaps, like a salesman who always expects you’ll agree with him.

......................................................ZEB

I think of him speaking in the superlative, which is quite the opposite of inquisitive manner you suggest. His experiences and ideas were always, “in-CRED-dible”, “ab-so-LUTE-ly MAR-vel-lous”, “BRIL-liant”. At first, the enthusiasm is infectious. In time it becomes quite tedious. Frankly, I couldn’t trust someone like that.

...................................................SHELLY

And overbearing.

....................................................PETER

A friend of mine’s father, who is a curator, said that Byars was the most egotistical artist he had ever worked with.

.................................................JONATHAN

Yeah, I guess so, but he was also manic-depressive. So you have to cut him some slack.

...................................................SHELLY

I don’t know. I’ve heard that he could be quite scary. I mean in a creepy, sexual kind of way. Can you excuse that?

Prop Department

A garage-like space with high ceilings is filling up with props. Company members have been making and gathering objects similar to those Byars used in his “plays”. Large, fabric pieces are hanging on the walls for storage. Smaller elements are arranged on tables under Plexiglas dust covers. There are photographs. A list like this one hangs on a cinderblock wall:

> Two gold flags—approx. 6 x 12 feet. The artist called these his “world flags.” They flew from the roof of a museum in Düsseldorf in 1986 as part of a “play”. We should make them.

> A 16-star American flag—approx. 6 x 30 feet. From an early performance (early 1970s). Two actors dressed as 19th-century presidents stood behind it. Byars used to tell people he was from Tennessee, which was the 16th to join the Union. We should sew this too.

> Broom—From a play in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; he swept and then gilded a stretch of the curb with members of the museum staff.

> Megaphone—In the 70s, among Byars’s most frequently used props. Standing on top of the Fridericianum Museum during the opening of Documenta 5 (1972), he yelled German first names through one. This performance introduced him to Europe.

> Burned book—Byars was upset by the design of the catalogue for his Berkeley Art Museum exhibition—his first major museum exhibition in the United States. Unannounced, and rather unceremoniously, he burned the catalogues in front of the museum to show his disapproval. Note: Do we do this on stage? It has other implications, you know.

> Perfume bottle—From a play in the Swiss Alps, The Black Drop of Perfume. The play consisted simply of the artist placing a few drops of perfume on a rock.

> Gold balls—Spheres represent a Platonic ideal for Byars, but they also evoke male sexuality. Phalluses and balls occur frequently in his work.

> Gold glitter—He placed it in letters he sent to patrons

Note: Try to superficially age some of the elements so they look as though they have been pulled from the garbage.

Wardrobe Department

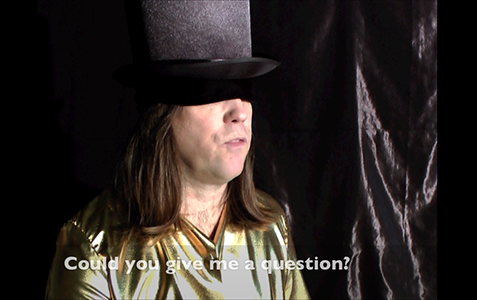

A chic unpainted concrete floor. A bank of narrow windows. The waredrobe department almost looks like a fashion boutique. In the center of the room is a star-shaped platform, bearing various suits and costumes, all based on Byars’s wardrobe but most altered beyond recognition. Byars performed frequently in elegant dress. Gold lamé. White linen. Black velvet. Red cotton and tulle. On a sidetable can be seen some black shoes, gloves, and mirrored glasses.

In 1969, with several dozen people in a Belgium gallery, Byars performed Pink Airplane (Pretend to Fly). The actors sat on the floor and placed their heads through pink fabric in the shape of an airplane. Byars then instructed them to close their eyes and pretend as though they were flying. A glammed-up version of the Pink Airplane hangs from the ceiling. On the wall below it, a hat for two, made from Japanese rice bags.

Script Department

Byars awoke every day before the crack of dawn to pen letters to current and would-be patrons—collectors, curators, and museum directors—proposing ideas for exhibitions, demanding assistance. Reading a Byars letter was a performance of sorts. You would open the envelope and a burst of gold glitter would spill to the floor. You would then unfold or uncrumple the hand-cut, precious papers to arrive at the text, written in Byars’ signature star-studded script. “Give me a show,” it might read, or “find someone to buy my work.” Faced with a request for an action, you would either comply or ignore it.

The script played a similar role in Byars’ more public performances. Generally comprised of a simple instruction or command, they could require performers to don a dress for four people, to “be quiet,” or to “pretend to fly.” A script was never longer than a phrase and sometimes as short as a single sound. In the Play of Death, the actors emerged onto the stage, uttered “Th”—an abbreviation for Thanatos, the Greek god of death—and disappeared.